Testing Guide

Summary

New functionality added to PlasmaPy must also have tests.

Tests are located in files that begin with

test_which are inside subdirectories namedtests/.Tests are either functions beginning with

test_or classes beginning withTest.Here is an example of a minimal

pytesttest that uses anassertstatement:def test_multiplication(): assert 2 * 3 == 6

To install the packages needed to run the tests:

Open a terminal.

Navigate to the top-level directory (probably named

PlasmaPy/) in your local clone of PlasmaPy’s repository.If you are on macOS or Linux, run:

python -m pip install -e ".[tests]"If you are on Windows, run:

py -m pip install -e .[tests]These commands will perform an editable installation of your local clone of PlasmaPy.

Run

pytestin the command line in order to run tests in that directory and its subdirectories.

Introduction

Software testing is vital for software reliability and maintainability. Software tests help us to:

Find and fix bugs.

Prevent old bugs from getting re-introduced.

Provide confidence that our code is behaving correctly.

Define what “correct behavior” actually is.

Speed up code development and refactoring.

Show future contributors examples of how code was intended to be used.

Confirm that our code works on different operating systems and with different versions of software dependencies.

Enable us to change code with confidence that we are not unknowingly introducing bugs elsewhere in our program.

Tip

Writing tests takes time, but debugging takes more time.

Every code contribution to PlasmaPy with new functionality must also have corresponding tests. Creating or updating a pull request will activate PlasmaPy’s test suite to be run via GitHub Actions, along with some additional checks. The results of the test suite are shown at the bottom of each pull request. Click on Details next to each test run to find the reason for any test failures.

A unit test verifies a single unit of behavior, does it quickly, and does it in isolation from other tests [Khorikov, 2020]. A typical unit test is broken up into three parts: arrange, act, and assert [Osherove, 2013]. An integration test verifies that multiple software components work together as intended.

PlasmaPy’s tests are set up using the pytest framework. The tests for a

subpackage are located in its tests/ subdirectory in files with

names of the form test_*.py. For example, tests for

plasmapy.formulary.speeds are located at

plasmapy/formulary/tests/test_speeds.py relative to the top

of the package. Example code contained within docstrings is tested to

make sure that the actual printed output matches what is in the

docstring.

Writing Tests

Every code contribution that adds new functionality requires both tests and documentation in order to be merged. Here we describe the process of write a test.

Locating tests

The tests for each subpackage are contained in its tests/

subdirectory. For example, the tests for plasmapy.particles are

located in plasmapy/particles/tests/. Test files begin with

test_ and generally contain either the name of the module or a

description of the behavior that is being tested. For example, tests for

Particle are located at

plasmapy/particles/tests/test_particle_class.py.

The functions that are to be tested in each test file are prepended with

test_ and end with a description of the behavior that is being

tested. For example, a test that checks that a Particle can be turned

into an antiparticle could be named test_particle_inversion.

Strongly related tests may also be grouped into classes. The name of

such a class begins with Test and the methods to be tested begin

with test_. For example, test_particle_class.py could define

the TestParticle class containing the method test_charge_number.

More information on test organization, naming, and collection is provided in pytest’s documentation on test discovery conventions.

Assertions

A software test runs a section of code and checks that a particular condition is met. If the condition is not met, then the test fails. Here is a minimal software test:

def test_addition():

assert 2 + 2 == 4

The most common way to check that a condition is met is through an

assert statement, as in this example. If the expression that follows

assert evaluates to False, then this statement will raise an

AssertionError so that the test will fail. If the expression that

follows assert evaluates to True, then this statement will do

nothing and the test will pass.

When assert statements raise an AssertionError, pytest will

display the values of the expressions evaluated in the assert

statement. The automatic output from pytest is sufficient for simple

tests like above. For more complex tests, we can add a descriptive error

message to help us find the cause of a particular test failure.

def test_addition():

actual = 2 + 2

expected = 4

assert actual == expected, f"2 + 2 returns {actual} instead of {expected}."

Tip

Use f-strings to improve error message readability.

Type hint annotations

PlasmaPy has begun using mypy to perform static type checking on

type hint annotations. Adding a -> None return annotation lets

mypy verify that tests do not have return statements.

def test_addition() -> None:

assert 2 * 2 == 4

Floating point comparisons

Caution

Using == to compare floating point numbers can lead to brittle

tests because of slight differences due to limited precision,

rounding errors, and revisions to fundamental constants.

In order to avoid these difficulties, use

numpy.testing.assert_allclose when comparing floating point numbers

and arrays, and astropy.tests.helper.assert_quantity_allclose when

comparing Quantity instances. The rtol keyword for each of these

functions sets the acceptable relative tolerance. The value of rtol

should be set ∼1–2 orders of magnitude greater than the expected

relative uncertainty. For mathematical functions, a value of

rtol=1e-14 is often appropriate. For quantities that depend on

physical constants, a value between rtol=1e-8 and rtol=1e-5 may

be required, depending on how much the accepted values for fundamental

constants are likely to change.

Testing warnings and exceptions

Robust testing frameworks should test that functions and methods return

the expected results, issue the expected warnings, and raise the

expected exceptions. pytest contains functionality to test warnings

and test exceptions.

To test that a function issues an appropriate warning, use

pytest.warns.

import warnings

import pytest

def issue_warning() -> None:

warnings.warn("warning message", UserWarning)

def test_that_a_warning_is_issued() -> None:

with pytest.warns(UserWarning):

issue_warning()

To test that a function raises an appropriate exception, use

pytest.raises.

import pytest

def raise_exception() -> None:

raise Exception

def test_that_an_exception_is_raised() -> None:

with pytest.raises(Exception):

raise_exception()

Test independence and parametrization

In this section, we’ll discuss the issue of parametrization based on an example of a proof of Gauss’s class number conjecture.

The proof goes along these lines:

If the generalized Riemann hypothesis is true, the conjecture is true.

If the generalized Riemann hypothesis is false, the conjecture is also true.

Therefore, the conjecture is true.

One way to use pytest would be to write sequential test in a single function.

def test_proof_by_riemann_hypothesis() -> None:

assert proof_by_riemann(False)

assert proof_by_riemann(True) # will only be run if the previous test passes

If the first test were to fail, then the second test would never be run. We would therefore not know the potentially useful results of the second test. This drawback can be avoided by making independent tests so that both will be run.

def test_proof_if_riemann_false() -> None:

assert proof_by_riemann(False)

def test_proof_if_riemann_true() -> None:

assert proof_by_riemann(True)

However, this approach can lead to cumbersome, repeated code if you are

calling the same function over and over. If you wish to run multiple

tests for the same function, the preferred method is to decorate it with

@pytest.mark.parametrize.

@pytest.mark.parametrize("truth_value", [True, False])

def test_proof_if_riemann(truth_value: bool) -> None:

assert proof_by_riemann(truth_value)

This code snippet will run proof_by_riemann(truth_value) for each

truth_value in [True, False]. Both of the above tests will be

run regardless of failures. This approach is much cleaner for long lists

of arguments, and has the advantage that you would only need to change

the function call in one place if the function changes.

With qualitatively different tests you would use either separate functions or pass in tuples containing inputs and expected values.

Test parametrization with argument unpacking

When the number of arguments passed to a function varies, we can use argument unpacking in conjunction with test parametrization.

Suppose we want to test a function called add that accepts two

positional arguments (a and b) and one optional keyword argument

(reverse_order).

Hint

This function uses type hint annotations to indicate that a and

b can be either a float or str, reverse_order

should be a bool, and add should return a float or

str.

Argument unpacking lets us provide positional arguments in a tuple or

list (commonly referred to as args) and keyword arguments in a

dict (commonly referred to as kwargs). Unpacking occurs when

args is preceded by * and kwargs is preceded by **.

>>> args = ("1", "2")

>>> kwargs = {"reverse_order": True}

>>> add(*args, **kwargs) # equivalent to add("1", "2", reverse_order=True)

'21'

We want to test add for three cases:

We can do this by parametrizing the test over args and kwargs,

and unpacking them inside of the test function.

@pytest.mark.parametrize(

"args, kwargs, expected",

[

# test that add("1", "2", reverse_order=False) == "12"

(["1", "2"], {"reverse_order": False}, "12"),

# test that add("1", "2", reverse_order=True) == "21"

(["1", "2"], {"reverse_order": True}, "21"),

# test that add("1", "2") == "12"

(["1", "2"], {}, "12"), # if no keyword arguments, use an empty dict

],

)

def test_add(args: list[str], kwargs: dict[str, bool], expected: str) -> None:

assert add(*args, **kwargs) == expected

Fixtures

Fixtures provide a way to set up well-defined states in order to have consistent tests. We recommend using fixtures whenever you need to test multiple properties (thus, using multiple test functions) for a series of related objects.

Property-based testing

Suppose a function \(f(x)\) has a property that \(f(x) > 0\) for

all \(x\). A property-based test would verify that f(x) — the

code implementation of \(f(x)\) — returns positive output for

multiple values of \(x\). The hypothesis package simplifies

property-based testing for Python.

Best practices

The following list contains suggested practices for testing scientific software and making tests easier to run and maintain. These guidelines are not rigid, and should be treated as general principles should be balanced with each other rather than absolute principles.

Run tests frequently for continual feedback. If we edit a single section of code and discover a new test failure, then we know that the problem is related to that section of code. If we edit numerous sections of code before running tests, then we will have a much harder time isolating the section of code causing problems.

Turn bugs into test cases [Wilson et al., 2014]. It is said that “every every bug exists because of a missing test” [Bernstein, 2015]. After finding a bug, write a minimal failing test that reproduces that bug. Then fix the bug to get the test to pass. Keeping the new test in the test suite will prevent the same bug from being introduced again. Because bugs tend to be clustered around each other, consider adding tests related to the functionality affected by the bug.

Make tests fast. Tests are most valuable when they provide immediate feedback. A test suite that takes a long time to run increases the probability that we will lose track of what we are doing and slows down progress.

Decorate unavoidably slow tests with

@pytest.mark.slow:@pytest.mark.slow def test_calculating_primes() -> None: calculate_all_primes()

Write tests that are easy to understand and change. To fully understand a test failure or modify existing functionality, a contributor will need to understand both the code being tested and the code that is doing the testing. Test code that is difficult to understand makes it harder to fix bugs, especially if the error message is missing or hard to understand, or if the bug is in the test itself. When test code is difficult to change, it is harder to change the corresponding production code. Test code should therefore be kept as high quality as production code.

Write code that is easy to test. Write short functions that do exactly one thing with no side effects. Break up long functions into multiple functions that are smaller and more focused. Use pure functions rather than functions that change the underlying state of the system or depend on non-local variables. Use test-driven development and write tests before writing the code to be tested. When a section of code is difficult to test, consider refactoring it to make it easier to test.

Separate easy-to-test code from hard-to-test code. Some functionality is inherently hard to test, such as graphical user interfaces. Often the hard-to-test behavior depends on particular functionality that is easy to test, such as function calls that return a well-determined value. Separating the hard-to-test code from the easy-to-test code maximizes the amount of code that can be tested thoroughly and isolates the code that must be tested manually. This strategy is known as the Humble Object pattern.

Make tests independent of each other. Tests that are coupled with each other lead to several potential problems. Side effects from one test could prevent another test from failing, and tests lose their ability to run in parallel. Tests can become coupled when the same mutable

objectis used in multiple tests. Keeping tests independent allows us to avoid these problems.Make tests deterministic. When a test fails intermittently, it is hard to tell when it has actually been fixed. When a test is deterministic, we will always be able to tell if it is passing or failing. If a test depends on random numbers, use the same random seed for each automated test run.

Avoid testing implementation details. Fine-grained tests help us find and fix bugs. However, tests that are too fine-grained become brittle and lose resistance to refactoring. Avoid testing implementation details that are likely to be changed in future refactorings.

Avoid complex logic in tests. When the arrange or act sections of a test include conditional blocks, most likely the test is verifying more than one unit of behavior and should be split into multiple smaller tests.

Test a single unit of behavior in each unit test. This suggestion often implies that there should be a single assertion per unit test. However, multiple related assertions are appropriate when needed to verify a particular unit of behavior. However, having multiple assertions in a test often indicates that the test should be split up into multiple smaller and more focused tests.

If the act phase of a unit test is more than a single line of code, consider revising the functionality being tested so that it can be called in a single line of code [Khorikov, 2020].

Running tests

PlasmaPy’s tests can be run in the following ways:

Creating and updating a pull request on GitHub.

Running

pytestfrom the command line.Running tox from the command line.

Running tests from an integrated development environment (IDE).

We recommend that new contributors perform the tests via a pull request on GitHub. Creating a draft pull request and keeping it updated will ensure that the necessary checks are run frequently. This approach is also appropriate for pull requests with a limited scope. This advantage of this approach is that the tests are run automatically and do not require any extra work. The disadvantages are that running the tests on GitHub is often slow and that navigating the test results is sometimes difficult.

We recommend that experienced contributors run tests either by using

pytest from the command line or by using your preferred IDE. Using tox

is an alternative to pytest, but running tests with tox adds the

overhead of creating an isolated environment for your test and can thus

be slower.

Using GitHub

The recommended way for new contributors to run PlasmaPy’s full test suite is to create a pull request from your development branch to PlasmaPy’s GitHub repository. The test suite will be run automatically when the pull request is created and every time changes are pushed to the development branch on GitHub. Most of these checks have been automated using GitHub Actions.

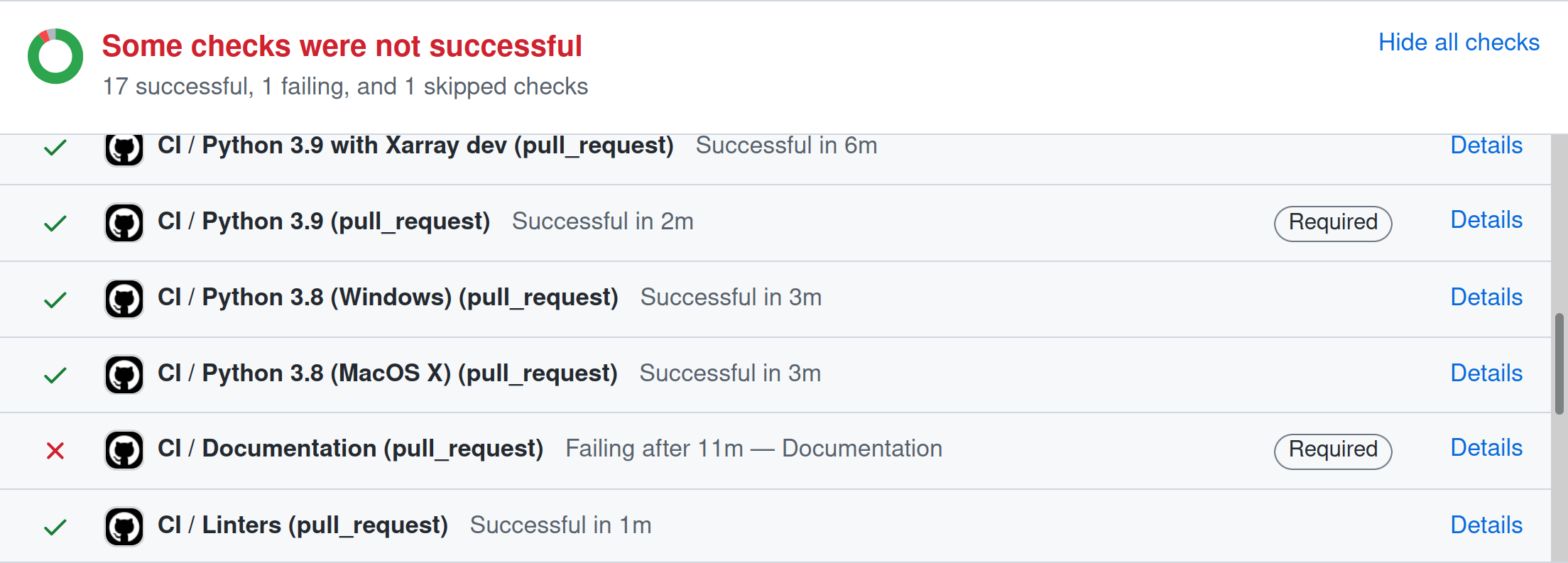

The following image shows how the results of the checks will appear in each pull request near the end of the Conversation tab. Checks that pass are marked with ✔️, while tests that fail are marked with ❌. Click on Details for information about why a particular check failed.

The following checks are performed with each pull request.

Checks with labels like CI / Python 3.x (pull request) verify that PlasmaPy works with different versions of Python and other dependencies, and on different operating systems. These tests are set up using tox and run with

pytestvia GitHub Actions. When multiple tests fail, investigate these tests first.Tip

Python 3.10, Python 3.11, and Python 3.12 include (or will include) significant improvements to common error messages.

The CI / Documentation (pull_request) check verifies that PlasmaPy’s documentation is able to build correctly from the pull request. Warnings are treated as errors.

The docs/readthedocs.org:plasmapy check allows us to preview how the documentation will appear if the pull request is merged. Click on Details to access this preview.

The check labeled changelog: found or changelog: absent indicates whether or not a changelog entry with the correct number is present, unless the pull request has been labeled with “No changelog entry needed”.

The

changelog/README.rstfile describes the process for adding a changelog entry to a pull request.

The codecov/patch and codecov/project checks generate test coverage reports that show which lines of code are run by the test suite and which are not. Codecov will automatically post its report as a comment to the pull request. The Codecov checks will be marked as passing when the test coverage is satisfactorily high. For more information, see the section on Code coverage.

The CI / Importing PlasmaPy (pull_request) checks that it is possible to run

import plasmapy.PlasmaPy uses black to format code and isort to sort

importstatements. The CI / Linters (pull_request) and pre-commit.ci - pr checks verify that the pull request meets these style requirements. These checks will fail when inconsistencies with the output from black or isort are found or when there are syntax errors. These checks can usually be ignored until the pull request is nearing completion.Tip

The required formatting fixes can be applied automatically by writing a comment with the message

pre-commit.ci autofixto the Conversation tab on a pull request, as long as there are no syntax errors. This approach is much more efficient than making the style fixes manually. Remember togit pullafterwards!The CI / Packaging (pull request) check verifies that no errors arise that would prevent an official release of PlasmaPy from being made.

The Pull Request Labeler / triage (pull_request_target) check applies appropriate GitHub labels to pull requests.

Note

For first-time contributors, existing maintainers may need to manually enable your `GitHub Action test runs. This is, believe it or not, indirectly caused by the invention of cryptocurrencies.

Note

The continuous integration checks performed for pull requests change frequently. If you notice that the above list has become out-of-date, please submit an issue that this section needs updating.

Using pytest

To install the packages necessary to run tests on your local computer (including tox and pytest), run:

pip install -e .[tests]

To run PlasmaPy’s tests from the command line, go to a directory within PlasmaPy’s repository and run:

pytest

This command will run all of the tests found within your current

directory and all of its subdirectories. Because it takes time to run

PlasmaPy’s tests, it is usually most convenient to specify that only a

subset of the tests be run. To run the tests contained within a

particular file or directory, include its name after pytest. If you

are in the directory plasmapy/particles/tests/, then the tests

in in test_atomic.py can be run with:

pytest test_atomic.py

The documentation for pytest describes how to invoke pytest and

specify which tests will or will not be run. A few useful examples of

flags you can use with it:

Use the

--tb=shortto shorten traceback reports, which is useful when there are multiple related errors. Use--tb=longfor traceback reports with extra detail.Use the

-xflag to stop the tests after the first failure. To stop after \(n\) failures, use--maxfail=nwherenis replaced with a positive integer.Use the

-m 'not slow'flag to skip running slow (defined by the@pytest.mark.slowmarker) tests, which is useful when the slow tests are unrelated to your changes. To exclusively run slow tests, use-m slow.Use the

--pdbflag to enter the Python debugger upon test failures.

Using tox

PlasmaPy’s continuous integration tests on GitHub are typically run

using tox, a tool for automating Python testing. Using tox simplifies

testing PlasmaPy with different releases of Python, with different

versions of PlasmaPy’s dependencies, and on different operating systems.

While testing with tox is more robust than testing with pytest, using

tox to run tests is typically slower because tox creates its own

virtual environments.

To run PlasmaPy’s tests for a particular environment, run:

tox -e ⟨envname⟩

where ⟨envname⟩ is replaced with the name of the tox environment,

as described below.

Some testing environments for tox are pre-defined. For example, you

can replace ⟨envname⟩ with py39 if you are running Python

3.9.x, py310 if you are running Python 3.10.x, or py311

if you are running Python 3.11.x. Running tox with any of these

environments requires that the appropriate version of Python has been

installed and can be found by tox. To find the version of Python that

you are using, go to the command line and run python

--version.

Additional tox environments are defined in tox.ini in the

top-level directory of PlasmaPy’s repository. To find which testing

environments are available, run:

tox -a

For example, static type checking with mypy can be run locally with

tox -e mypy

Commands using tox can be run in any directory within PlasmaPy’s repository with the same effect.

Code coverage

Code coverage refers to a metric “used to describe the degree to which the source code of a program is executed when a particular test suite runs.” The most common code coverage metric is line coverage:

Line coverage reports show which lines of code have been used in a test and which have not. These reports show which lines of code remain to be tested, and sometimes indicate sections of code that are unreachable.

Tip

Use test coverage reports to write tests that target untested sections of code and to find unreachable sections of code.

Caution

While a low value of line coverage indicates that the code is not adequately tested, a high value does not necessarily indicate that the testing is sufficient. A test that makes no assertions has little value, but could still have high test coverage.

PlasmaPy uses coverage.py and the pytest-cov plugin for pytest to

measure code coverage and Codecov to provide reports on GitHub.

Generating coverage reports with pytest

Code coverage reports may be generated on your local computer to show

which lines of code are covered by tests and which are not. To generate

an HTML report, use the --cov flag for pytest:

pytest --cov

coverage html

Open htmlcov/index.html in your web browser to view the coverage

reports.

Excluding lines in coverage reports

Occasionally there will be certain lines that should not be tested. For

example, it would be impractical to create a new testing environment to

check that an ImportError is raised when attempting to import a

missing package. There are also situations that coverage tools are not

yet able to handle correctly.

To exclude a line from a coverage report, end it with

# coverage: ignore. Alternatively, we may add a line to

exclude_lines in the [coverage:report] section of

setup.cfg that consists of a

a pattern that indicates that a line be excluded from coverage reports.

In general, untested lines of code should remain marked as untested to

give future developers a better idea of where tests should be added in

the future and where potential bugs may exist.

Coverage configurations

Configurations for coverage tests are given in the [coverage:run]

and [coverage:report] sections of setup.cfg. Codecov

configurations are given in .codecov.yaml.

Using an integrated development environment

Most IDEs have built-in tools that simplify software testing. IDEs like PyCharm and Visual Studio allow test configurations to be run with a click of the mouse or a few keystrokes. While IDEs require time to learn, they are among the most efficient methods to interactively perform tests. Here are instructions for running tests in several popular IDEs: